painted doors? german words? we’ve got it all this time.

I’ve written before about how I’ve never really considered myself a sport scientist until I read this paper, and I’d say that even though my job title contains those two little words, it still doesn’t sit quite right with me.

I found myself standing alongside a coach early on into my new job, one of my favourite places to be. I feel being side by side in context, watching a problem unfold together is where the most amazing things emerge. No (intended) hierarchy, just two people trying to observantly participate in the world. In my interview, I was asked how I know I’m making ‘progress’ with a coach, and the answer I’ve been giving lately is “when they ask me a question I didn’t see coming”.

Why this particular, arbitrary benchmark? Well, there’s so much in a question. I can tell where your attention is, what you value, if you’re curious, if you believe in right and wrong or linear causation, all from the way a question is asked. It’s like another language, where the words don’t directly translate. There is meaning in and around and between the roots of the word, and a question feels like meaning bubbling to the surface.

I’ll be honest with you, I ran to our friendly neighbourhood search engine to try and find a German word that would be a perfect example here, and I stumbled upon a scarily accurate one. Like somehow I was supposed to find this word not just for this newsletter, but because I’ve been feeling this for the last few months. The word is torschlusspanik, which roughly means “the fear that time is running out and you’re about to miss some important opportunity.” Literally, it translates to gate-closing (torschluss) panic (panik), like a door closing.

I feel like the work I primarily do as a sport scientist is a series of doors, and as Biesta (2025) writes in their recent paper, education is about opening doors.

Our work is always to open doors, particularly where students didn’t even know that there was a door, and each time we open the door to the world, we also open the door to the self.

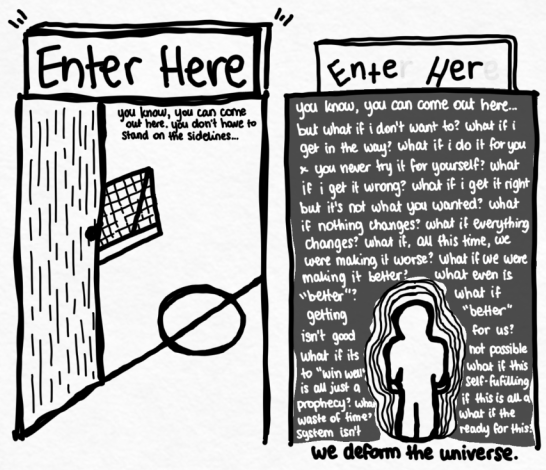

As I participate in training sessions across various sports with unique coaches, I can feel these doors opening and closing. I’ve actually used this analogy twice before in my own thinking/writing/drawing around my work:

when trying to connect with a coach and their sport program, walking into the room felt like when you knock on someone’s door and you catch them at a bad time; hands full, running after a small child, and everything on their face says ‘please dear lord not another thing’.

a coach invites me onto the field at their training session, saying “you don’t have to stand on the sidelines”. This is a momentous occasion, but I don’t step through that door on this day. Instead, I stand frozen on the sideline, paralysed by doubt.

These are not the open doors that Biesta talks about, but we often preface in learning design/skill acquisition that rich opportunities are possible when we are welcomed in, so those open doors are the first step. I mean, my family is from Transylvania, and everyone knows that you should never invite a vampire in 😂

Questions, to me, are doors but not quite solid ones. One of my all-time favourite novels is The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern, and the gorgeous, mind-boggling worldbuilding in this book is centred on painted doors. Stay with me, I promise it’s worth it. Without giving too much away, there is a character in the book who paints lifelike doors that look strangely like graffiti to those passing by. But what this passer-by doesn’t know until they reach for the handle is that this door has been crafted specifically for them, and it is an invitation to a world that exists below the surface – if they are willing to reach out and touch it.

I won’t go into invitations and affordances this time around, but these invitations for action are a key component of the theoretical framework that I use, and as you can see by the stories I’ve been weaving thus far, this theory is deeply entangled with who I am, what I notice, how I directly perceive the world around me, and what I believe is important. It also helps me appreciate that everyone will have their own versions of seeing the world and the point isn’t to be right or wrong, it’s to know that our ideas are connected to something.

I like to describe this as a tether, like being out on a spacewalk while attached to the space station. It’s not up to you to reinvent the wheel, but blending your rich experiences and the knowledge you grow along the way with the fertile garden that has been growing this whole time, planted long before you, is an incredible space for new things to emerge. Again, this doesn’t privilege experience or experimental, but rather reminds us that there is so much to learn when we stir them both in.

This thought spiral all started with a coach asking me a question: “how do we know what is important about my sport?”

Shit, I can barely grasp the rules! But surely between us, we can search for the answer together. So I organised a whiteboard session after training, where we could brain dump everything they thought could contribute to performance in the space they know intimately, while I sketched it all out, adding the occasional commentary when we seemed stuck on what this variable meant or what it looks like at training and on game day. At one point, we were talking about throwing the ball, and the tension between wanting to have a consistent outcome when releasing the ball while knowing that “I’m not a robot”, so getting into the exact same position every time is both nearly impossible and not the point.

The door appears, painted on the wall next to our whiteboard, and I reach out to open it.

At this point, I know just enough about the people in front of me to offer a suggestion. I draw a squiggly rectangle in a diagram of where the approximate throwing location is for the athlete and begin talking about functional variability, but not in those words. The phrasing that leaves my mouth, for the first time, is “finding the place to throw from”. I’ve surprised myself at this point, and I had no way of knowing at the time, but this line of thinking will reverberate through 8 weeks of conversations at training. In this time, it has also shaken loose so many other lines of thinking, things that only emerged as we started ponding how to find where to throw from in diverse scenarios. This variability manifests in so many ways across the throwing arm itself, how the body is aligned, what they are targeting and by extension, where their attention is as they let go of the ball.

Like plucking a guitar string, for some reason, that sound has been playing for almost 2 months through very little explicit maintenance other than paying attention and being present. It sounds a little silly when I put it like that, but I am now seeing this single string become a chord, as we discover other related problems to solve, and the strings begin to resonate together.

As this moment unfolded, I was left wondering how many different ways this could have gone, how many other painted doors were out there. I also felt my own question forming at the edges of my mind, namely: who gets to decide what is worth knowing?

At any point in this interaction, I could have taken the lead. I could have directed the entire conversation by writing up what I thought the key performance variables of this sport are based on the (scarcity of) research that exists in this space, perhaps borrowing from other sports to fill in the gaps and launch into a lecture about the theory that I use. But I have never been the kind of person to do this, because I don’t think it serves any value to force-feed that information – to throw it at a closed door and effectively, make sure it never opens as it locks from the inside with a little ‘click’.

But that doesn’t mean that the theories I use are not important. And almost more importantly, just because a coach may/not be to tell me their theories of choice, that doesn’t mean they don’t have one. It is not my intention to change their mind, to ‘convert’ them, to undertake an evangelical crusade about why the way I happen to see the world is the only explanation worth knowing. This distinction is important, and sits at the heart of my dissatisfaction with the academic world of late → by positioning things as artificially dichotomous at the wrong levels, we are saying that something is more valuable than something else, that one theory is worth more than another.

Now, un/fortunately, we currently exist in a world where many of the theoretical frameworks we work with or interact with day to day were given to us, buried so deep that we forgot they were there, unwilling to exhume the bodies of knowledge that we’ve centred our universe on. The problem is not what they are, again to avoid any unnecessary heralding, but the fact that they have been largely unexamined. You know Socrates quote…

I want to come back to the idea of the wrong levels, because it bears unpacking. I am often asked if coaches can “pick and mix theories” (which greater minds than mine have discussed this here), and I feel like this question and it’s phrasing alone is very symptomatic of the path-dependency and unexamined life I’ve been pondering here. There are distinct points of divergence between each theoretical framework, they wouldn’t exist as multiple theories otherwise. As such, it helps to know which path our line of thinking and practice follows. As a coach, you already have a theory of the learner and what learning is. You appraise what they do, what has happened, and what to do next in particular ways. These ideas are tethered to something, they always are. The question is, do you know to what?

If we continue to ponder this “pick and mix” question at the level of practice designs in a training environment, then we will continue to expertly dodge the root of this question, which is how do we know what do to (next) as coaches? You might think you can answer that question with a perfectly curated session plan, but this tool alone can be used infinitely, with various connections to different theories. It was never really about the tools, because if you had an informed version of what learning can be, and how your training design connects to this, then you wouldn’t be “picking and mixing”. You would know (or continue to find) that some things within your practice would help align you to the goal of developing others and others won’t, based on how you think learning occurs. It is our inability to distinguish our alignment that allows this question to dig its roots in.

At this point, you might be wondering about the title of this edition, and I wanted to give you the backstory. I recently had the immense pleasure of hearing Sam Robertson speak live at a(nother) panel, and I’ve always admired his clarity in thinking and ability to ask the kind of questions that cut you in two. I was looking forward to thinking out loud about “who gets to decide what’s worth knowing” with him, but as the question hung in the air, I received an exasperated sigh followed by today’s title: “do we really need this?”.

In a way, this newsletter is a love letter to my answer at the time, which is: unequivocally yes. We do need this, and not because I think we need trading cards of everyone in sport with their characteristics and theoretical framework on the back. I think we need this because we are lost, untethered, trying to follow a breadcrumb trail home that has been blown away, leaving us wondering where on earth to go next out of fear, not curiosity. I think we need to ask more questions like “who gets to decide what’s worth knowing” because we leave it unspoken too often. We don’t stop to wonder if our direction of travel is actually taking us towards or further away from our goals until an end of season review, forgetting about all the moments, the music, along the way.

I mean, the fact that I’m even willing to pose such questions is inspired by how I tentatively answer the question of “what is knowledge”: something that is not acquired before we go but rather forged alongside others, where we see, feel, hear, smell and taste things for ourselves by actively participating in our broader ecology and joining in with the activities of experienced others (surprise! same paper again). Is this the line I give to others if they would ever ask me? Sometimes. There are so many versions of it that only emerge when I am asked, by that person, at that time, in that setting, but I am constantly learning where that version is tethered to.

Is everyone ready to ponder this? Probably not, but that doesn’t mean we should sit idly by. Every correspondence I have is in some way coloured by all of this and more. I want to be the kind of practitioner that people trust with their beliefs, assumptions and values not so I can wield them in some way, but rather so I can know them better, to join in with them. I need to know enough to follow their path of thinking and knowing and being so I can be there alongside them, and point out the painted doors along the way.

Leave a comment